Flowing Crimson investigates the contextualisation of menstrual taboos in religious texts and how it influences the contemporary understanding of menstruation. Menstrual myths still persist in various communities in India. In these communities, the menstruating body is seen as impure, dirty or dangerous and accordingly, prohibitions are placed on the individuals. Menstruating females are forbidden from religious spaces, not allowed to carry out daily chores and sometimes secluded from other members of the community. These views stemmed from both ancient beliefs and a lack of scientific information. As traditions go, these have been passed through ancestry in a form of hearsay. Today, while the myths persist, the religious and socio-cultural origins of these practices lay forgotten. Their relevance is hence neither reflected upon nor questioned.

Taking upon the question of ‘what is menstruation?’, this piece recalls a narrative from the Bhagvata Purana (one of the most sacred texts in Hinduism) regarding Lord Indra, which addresses the origins of the menstrual cycle.

According to the legend,

Once upon a time Lord Indra, the King of Heavens and all Gods got into a violent feud with his teacher, Guru Brahaspati. The Asuras (demons) taking advantage of this feud attacked Indra’s kingdom and forced him to flee.

Indra sought the advice of Lord Brahma on how to win his kingdom back. Upon Brahma’s guidance, Lord Indra appointed a new teacher, Vishwarupa. Vishwarupa was the son of God Tvastha (the artisan God) and a renowned Brahmana (a learned scholar and priest). However, his mother was an Asura (demon) and his loyalties were divided between the Devas (gods) and the Asuras (demons). As time progressed, Vishwarupa started to notice that Indra and the Devas spent an inordinate amount of time in pursuit of pleasure. Secretly, he started giving a portion of the sacrificial offerings to the Asuras. As a result, their strength increased. When Indra came to know of this treachery, he became very angry. Without pausing to think of the consequences of his actions, he slayed Vishwarupa. In his fury, Lord Indra had however committed the heinous crime of killing a Brahman and inflicted upon himself the blame of Brahmahatya, the sin of killing a Brahman.

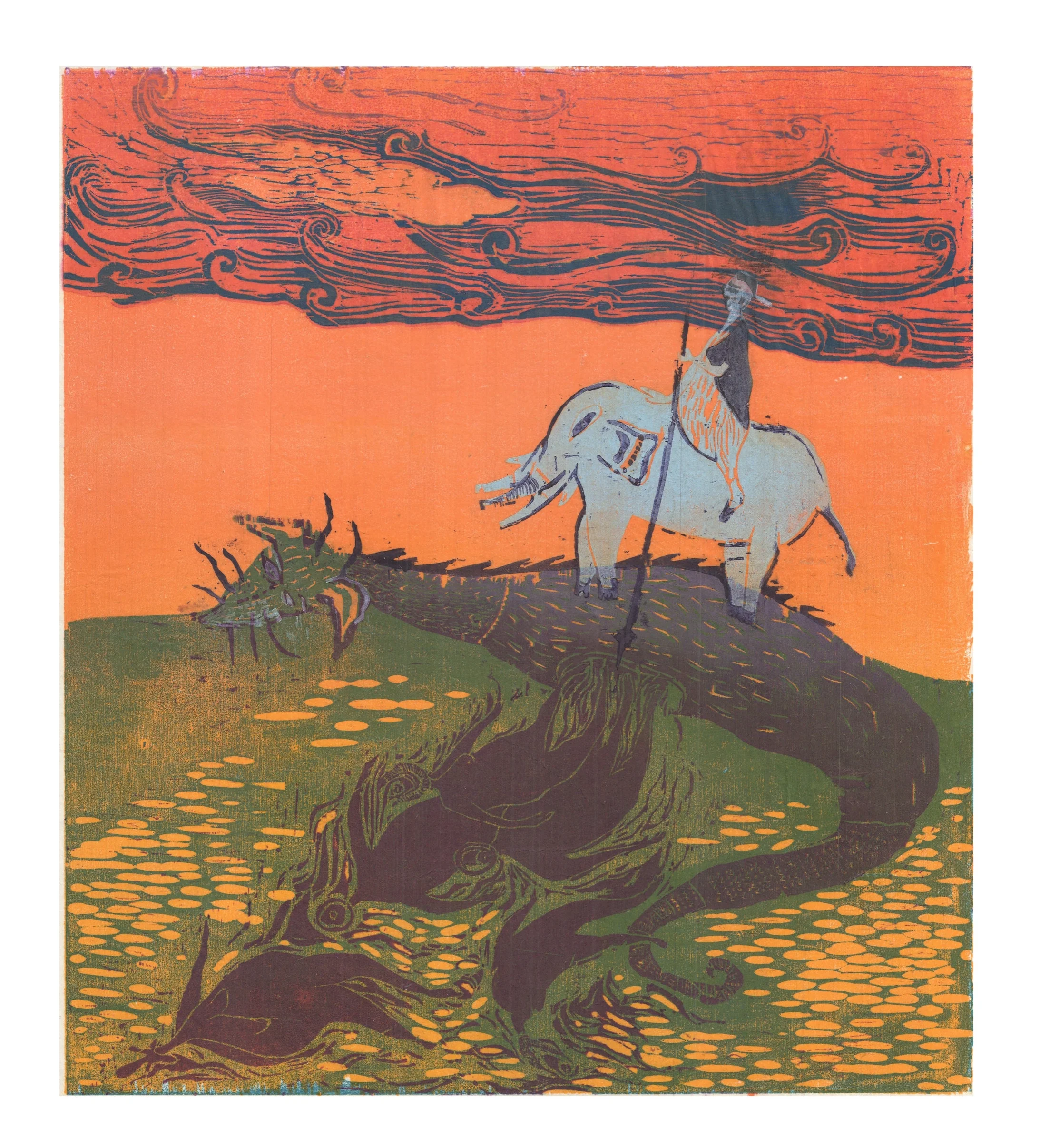

Meanwhile, seeking revenge for the murder of his son, God Tvastha fashioned Vritra, a demon dragon that would chase and haunt Indra of his sin. Scared, Indra sought to redeem himself. In order to get rid himself of Brahmahatya, Indra was advised to distribute the sin amongst the trees, water, earth and women while also presenting each element with a boon. Women received their portion of the sin in the form of their menstrual cycles. As a boon, they were granted increased sexual pleasure and fertility.

In the olden days with the absence of proper sanitation, health and hygiene of the women were a concern and seclusion was encouraged. Religious texts were often used as a precedent to ensure that the practice was followed. The above narrative calls to mind how a scientific and natural bodily process became characterised to be shameful and immoral. Today, this practice seems redundant. Whilst the narrative has eluded the present generations, the association of periods with sin and guilt runs deep within societal norms, so much so that it isn’t even openly discussed. The stigmatisation prevents the needs of women from being voiced and implemented. In recalling this myth, Flowing Crimson traces how these associations have come to form as part of the cultural history. It questions that who should have agency over how the female body should be discussed, the spaces it can occupy or simply how it should exist. Should we upkeep traditions that seem harmful and redundant?